About 10 years ago, the interview process of software engineer is pretty simple and straightforward: if you meet the condition, you will be invited on-site. The interviewer will ask you some questions about previous or current projects, computer science basic knowledge, and so on. If you are a fresh graduate, maybe there is a paper test about algorithm. Then if the interviewer think you are an appropriate candidate, you will enter the next round, mostly final round interview. This round always involves with R&D Director/HR, little or no technical discussion, only for salary and to see whether you can fit the culture of the team. Generally speaking, the whole process only lasts for 1 week and is comprised of 1 ~ 2 rounds. no-nonsense!

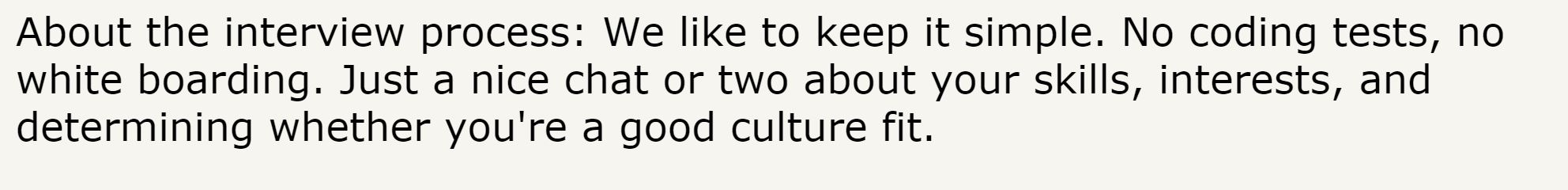

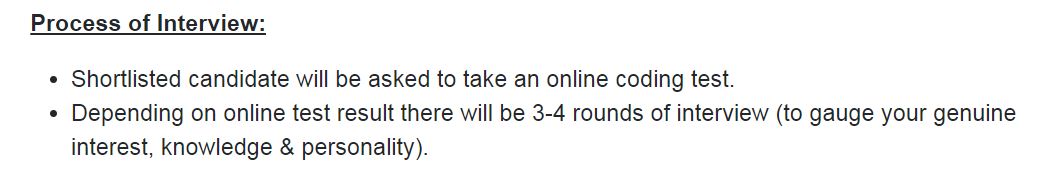

If you want to know contemporary interview process, please check following capture of a job description, and I think it is a good represent:

Currently, before you reach on-site, you should have already passed 2 ~ 3 rounds of interview. Usually, the phone screening will be the first round, and HR will get a rough knowledge of your background. Sometimes HR also will ask you some technical questions though he/she is not technical-orientated. Then HR will notify there is a coding/homework test which you should finish by a deadline. Sometimes, the phone screening can be omitted, and a mail which notifies you need finish coding/homework test comes to your mail-box directly. It gives me (or maybe you) an impression that the persons in company are very busy, and there is no time to talk crap with interviewees. You apply for job, not job applies for you, Correct? So you should finish some work to prove you are qualified to talk to the company. Alas! I once got a homework test whose document is 7 pages! Yes, 7 pages! Besides coding, I also need to write a detailed test plan. The whole task costed me 30 hours, and I even doubt the company just outsourced its work to a free labour. Anyway, if you pass this round, you can hear the voice or see some person at least; if not, you will receive a rejection letter or no any response. The game is over, and you can’t even talk one word with the company.

In some cases, there is an extra coding interview before on-site. You passed online coding interview just now, but this time you will share a screen with interviewer to test your “pair-programming” ability. During this process, you should interact with interviewer actively: pose something, confirm something, etc. I don’t know whether this is the essence of “pair-programming”.

If you arrive this stage, congratulations! You can be invited on-site. There may be another 2 ~ 4 rounds of interview: every interview will cost 1 ~ 2 hours., and the content is nothing more than following 4 categories:

a) Still coding test (e.g., a dynamic programming problem);

b) System design (e.g., how to design a car-parking lot?);

c) Computer science basic knowledge (e.g., the difference between TCP and UDP?) ;

d) You previous/current projects (e.g., what is your current working field?).

There seems no standard of the interview, and you don’t know you should answer how many questions correctly to guarantee you can enter the next round, especially many problems are open-minded.

Based on previous description, you can see to get a job offer today, you will endure 4 ~ 6 rounds of interview, and nearly ~10 hours (this doesn’t count the time you spend on homework or prepare for online coding) in total. The whole process can last for 1 ~ 2 months. I can’t say this method is correct or not, but it indeed boosts the time cost of candidate at any rate. Regarding the companies: is it really meaningful for so many rounds? What result do you expect for every round? The candidate who passes all rounds is in truth a right person? If you are a owner of a company and can get specific answers for above questions, I think you can know whether this interview method is suitable or not for your corporation.

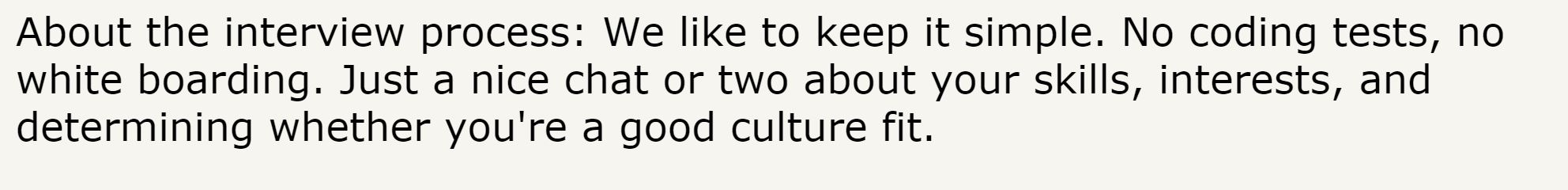

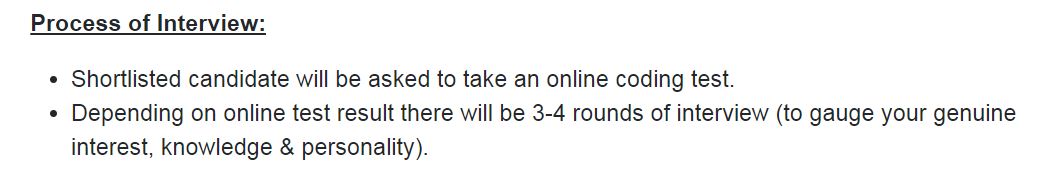

BTW, I really like following interview process: